New research says early failure in the sciences may be beneficial in the long run.

In 1968 ROBERT MERTON, a sociologist at Columbia University, identified a feature of academic life that he called the Matthew effect. The most talented scientists, he observed, tend to have access to the most resources and the best opportunities, and receive a disproportionate amount of credit for their work, thus amplifying their already enhanced reputations and careers. Less brilliant ones, meanwhile, are often left scrambling for money and recognition.

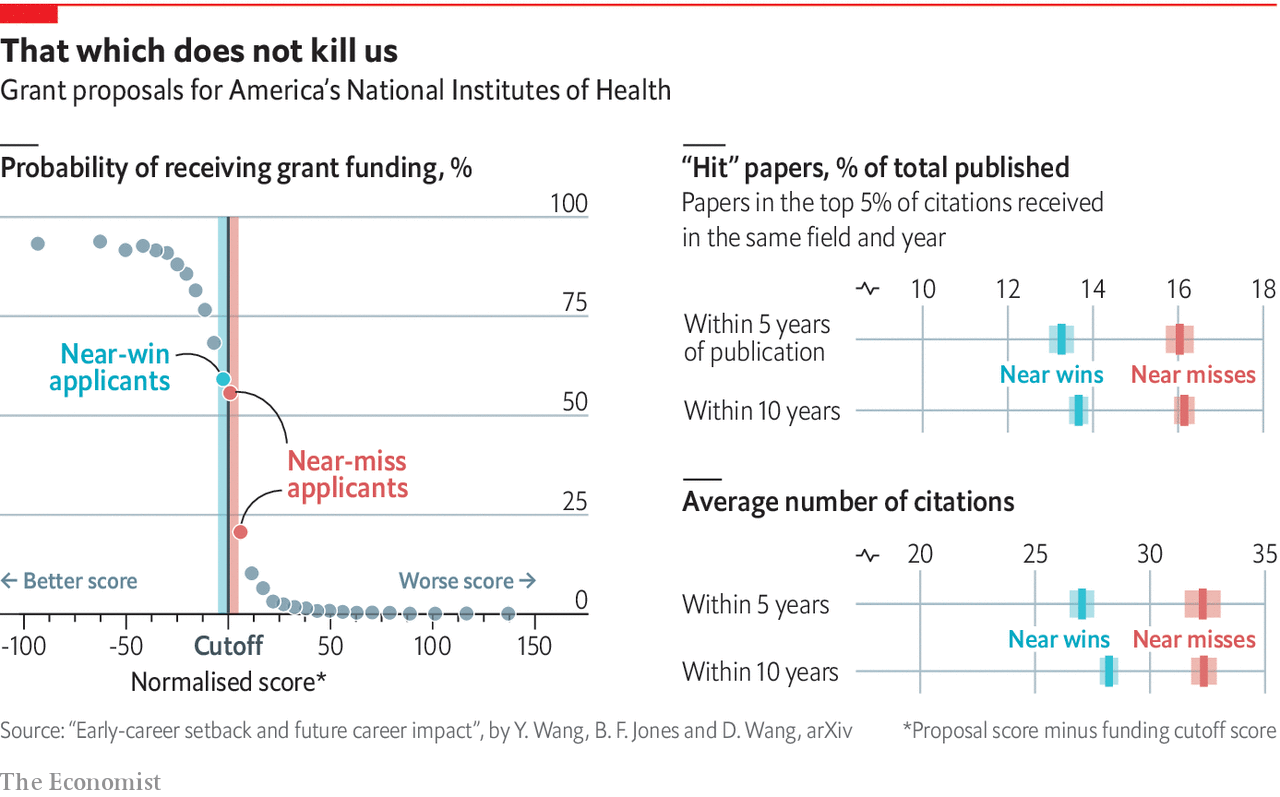

New research suggests this may not tell the whole story. A working paper by Yang Wang, Benjamin Jones and Dashun Wang of Northwestern University finds that success in the sciences does not always breed more success, and that scientists who fail early in their careers may benefit from the experience. The authors discovered this by collecting data on grant applications submitted between 1990 and 2005 to America’s National Institutes of Health (NIH) by junior-level scientists. In particular, they focused on two groups of applicants: those who received relatively high scores on their submissions but just missed getting a grant, and those who scored similarly well but just succeeded in being awarded one.

While some of this can be explained by the weakest scientists in the no-grant group giving up, the three researchers showed that other, unobservable, characteristics such as “effort” or “grit” are also at work. Overall, the authors conclude, the findings are consistent with the concept that “what doesn’t kill me makes me stronger”.

May 10th 2019

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário